Almost every morning, as I sit at my desk, I watch the sky turn from dark blue to bright yellow over Joubertspiek, the gable-shaped rocky hill next to Simonsberg. Yet I’ve never thought much about the origin of the name Joubertspiek – Joubert’s Peak. That changed over the Christmas break last year, when I found myself in search of some holiday reading.

I’m an economic historian. Most of my research focuses on the early Cape Colony. So when I came across a new novel set in that period – not another heavy economic history treatise, but one promising to be ‘a sweeping story of love, adventure and adversity’ – I thought I might as well give it a try. I was unaware that the book – The Map of Bones – was actually the fourth and final instalment in Kate Mosse’s Joubert Family Chronicles. So, as the family and I made our way to the beach – yes, December is summer in South Africa! – I purchased the first novel, The City of Tears, for my Kindle. And, as my wife can confirm, I got stuck in. Most mornings, often as early as 3 am, I was reading. I finished all four books in ten days.

I particularly enjoyed books one and two. The characters felt more grounded, their struggles more believable. I was familiar with Huguenot history, but most of what I knew was limited to the period after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 – when Louis XIV withdrew the protections once granted to Protestants, triggering renewed persecution and mass emigration. What I had not fully appreciated was the world that came before: the uneasy toleration that shaped the lives of those whose children’s children would one day become refugees.

I knew this because some of my ancestors are Huguenots. As I explain in this post, ten generations ago, the eighteen-year-old Louis Faurite trekked from his native France through Switzerland and Germany to Amsterdam, only to take a ship to the southern tip of Africa and build a new life. His story also inspired some of my research on the topic. With Dieter von Fintel, I investigated the economic impact of the Huguenots in South Africa. A brief takeaway: they were more productive wine farmers than the Dutch settlers. To prove that this was because of the viticultural skills they brought from France, we compared Huguenots from wine-producing regions against those from non-wine-producing regions. Those from wine-producing regions were significantly more productive. (We’re working, with former Master’s student Christiaan de Swardt, to examine why those skills persist for multiple generations. Hopefully more on that soon.)

Reading The Map of Bones, though, made me want to go back to the sources. Some of the characters are historical figures, and I wondered what happened to these refugees after they arrived at the Cape. To answer that question, I turned to a new dataset we’ve been collecting over the last decade. (For more about this project, visit the Cape of Good Hope Panel website.) In what follows, I focus only on one district – Stellenbosch-Drakenstein – the area where Pierre Joubert and his wife Isabeau first settled.

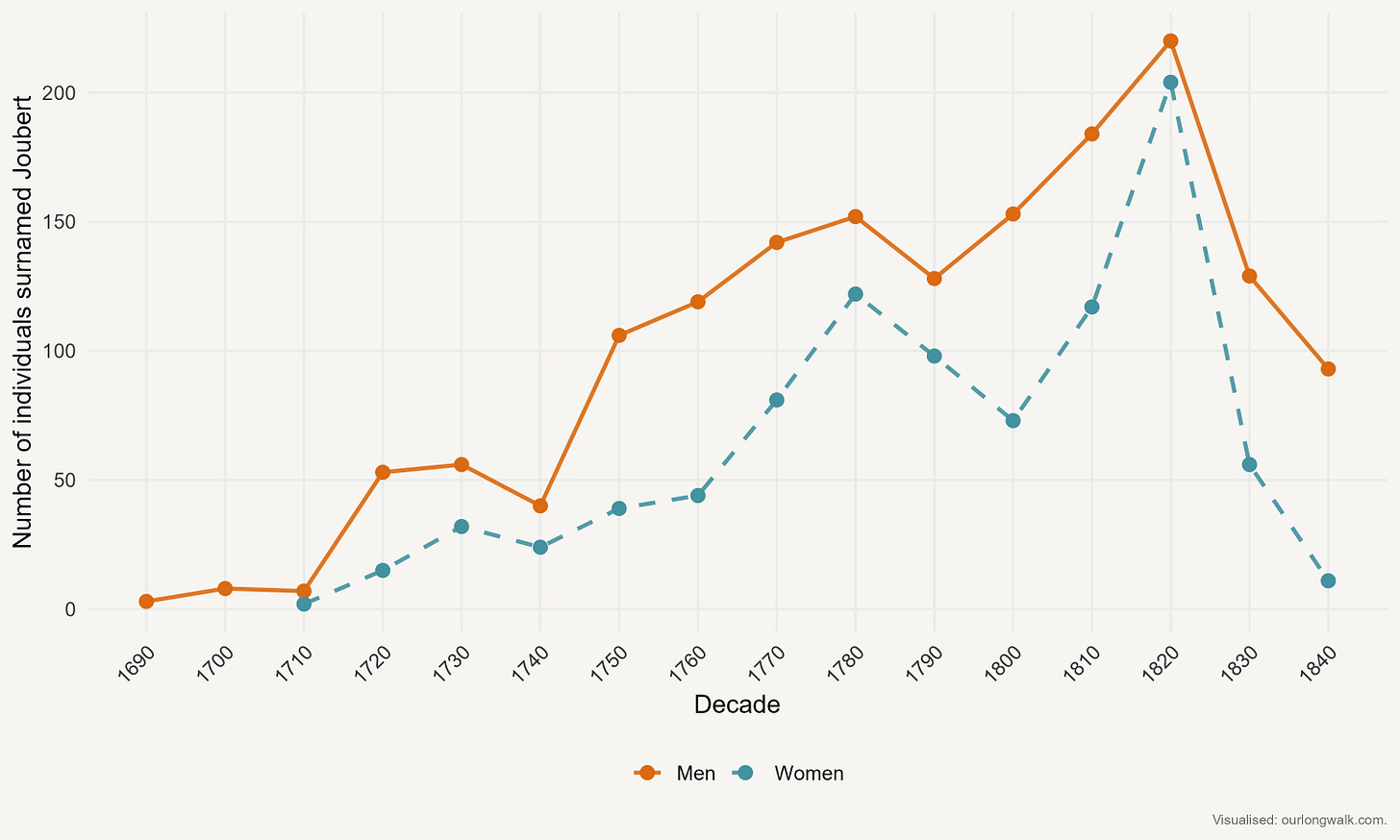

Pierre and Isabeau (Jaubert, as it is spelled in the book) are two of the historically accurate refugees that join the fictional Suzanne Joubert as refugees to the Cape. Their presence quickly became visible in my records. In the first figure below, I simply show the number of male and female Jouberts at the Cape. (These are decade totals, so it could be that the same household appear several times within the decade total.) What is clear is that they became important inhabitants of the district over the eighteenth and into the nineteenth century. The decline towards the end is the result of falling population numbers as districts split off, so I would not read too much into that.

Suzanne Joubert first meets Pierre and Isabeau on board the ship. She later visits them on the then-border of the Colony (p. 246–247):

At dawn, they stopped to rest the horse and to eat.

‘Do you know where your friends are building their farm?’ Harrie asked.

‘Only that they were one of four families allocated land in the valley close to the Simonsberg mountains.’

He nodded, though his eyes seemed unfocused. ‘We will find them.’

It was nigh on eleven o’clock in the morning by the sun, when the footsore and weary party saw a small rectangular hut on the horizon nestled in the fold of two hills. As they drew closer, the outline of the building became clearer. Suzanne thought it looked more like a hide for hunters than a home, but attempts had been made to make it presentable: a flat, matted straw roof; clay walls; a generous window with a wooden shutter and a small bench beneath it. Two earthenware pots stood on either side of the single door. Suzanne smiled, remembering Pierre Jaubert’s protestations at the idea that his wife would have to manage with only half a cooking pot and s third-share in a plough. Now she was out here in this boundless space, it seemed even more absurd that the settlers would have to divide these basic assets between them. How could they share between them when teh plots of land were so far apart and the farming seasons the same for each family?

All the same, she had faith that Pierre and Isabeau would make the best of it. And, sure enough, once they were within hailing distance, she saw a makeshift fire with a brace suspending an iron cooking pot. A little further away, a plough with dirt in its teeth suggested Pierre was working hard to till the land. And behind the clay hut, she saw a basic pen with two cattle sheltering from the heat beneath a young karee tree.

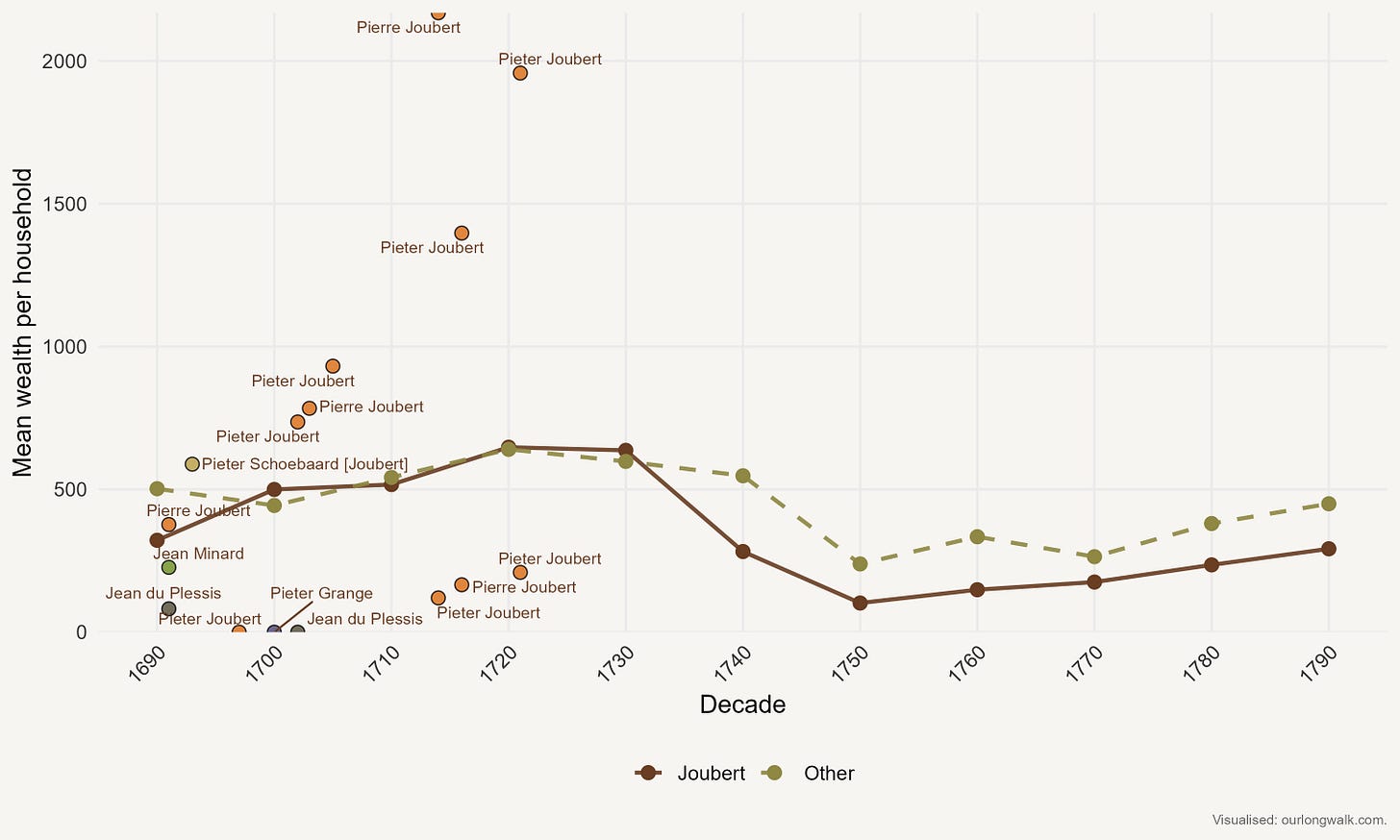

In the very first census that includes Pierre Joubert, he indeed had only a few assets. In the figure below, I plot all the Pierre or Pieter Jouberts in the annual tax censuses of the district against their total agricultural wealth (mainly wheat, wine and cattle). I also plot some of the other historical characters that feature in the book, and show the average wealth of all the Jouberts versus other settlers.

Mosse’s description of Pierre Joubert’s initial poverty continues (p. 248):

‘Oh. Well, you must come inside. Tell me how you come to be here. I wish Pierre was at home. He has gone to visit Monsieur Grange and Monsieur Malan on the far side of the valley.’ She shook her head. ‘The soil here is no good. My husband hopes to persuade them to join with him and petition the commander to allocate better more fertile land beside the Berg River.’

‘That is where we are headed, to Olifantshoek.’

Olifantshoek, today’s Franschhoek, is indeed where the Jouberts would settle after their initial hardship. They established La Provence in 1694 and La Motte in 1709. Success came soon. Consider the upward trajectory of the dots in the graph above. (Another Pieter or Pierre Joubert appears in the 1710s. This might have been a son or cousin.)

Success meant expansion. They returned to their original valley, for example, acquiring Bellegam (1700) and Lormarins (1723) in Groot Drakenstein; Winterhoek (1716) and La Roque (1723) in Klein Drakenstein; a property near Kruishof (1732) in Achter-Groenberg; and, in the region known then as Land van Waveren – later the Tulbagh district – the farms La Plaisante (1710) and Montpellier (1723).1

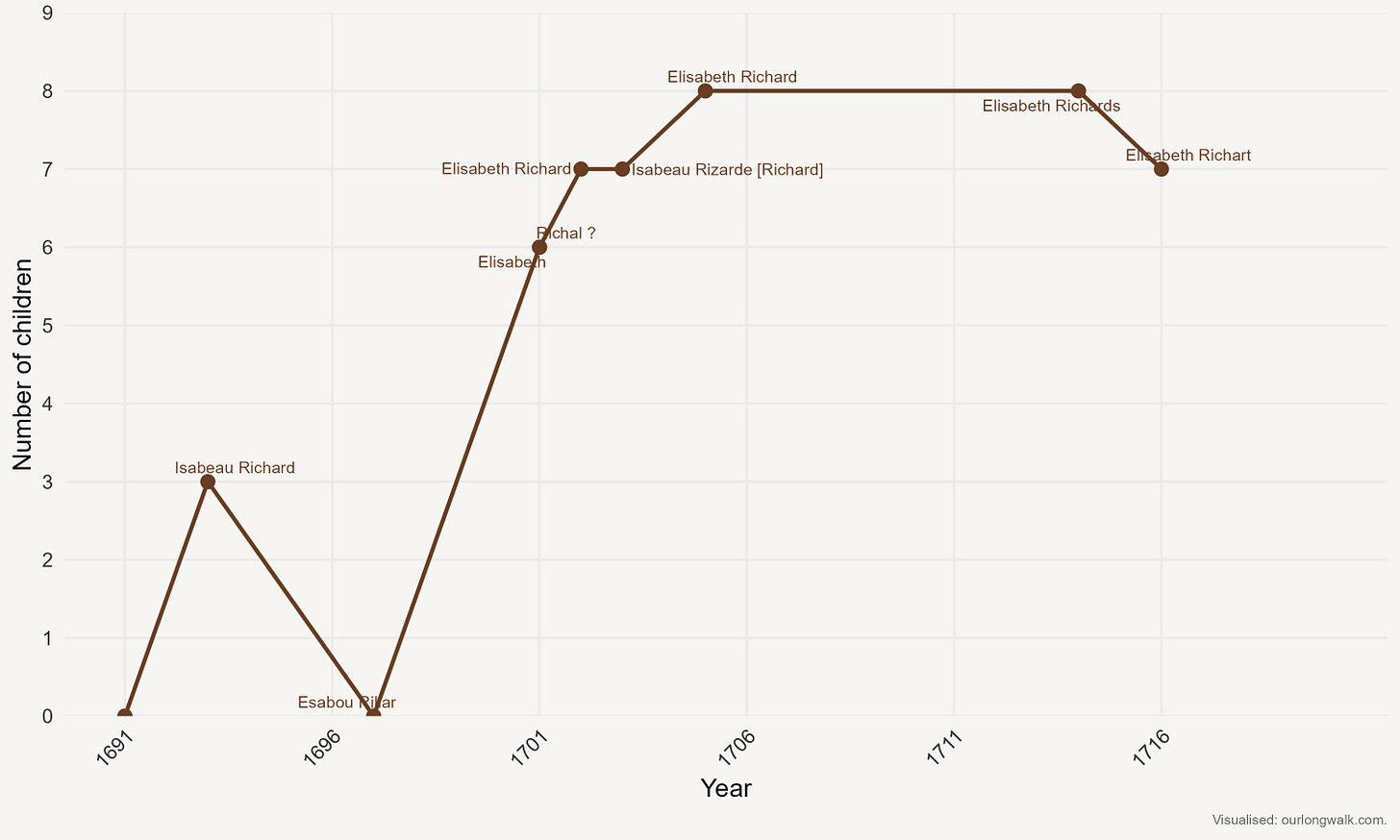

More land meant larger households. In the next figure, I show the number of children in the household. I also show the various spellings of Isabeau’s name recorded in the tax returns. (Also note above that ‘Joubert’ in the 1710 census became ‘Schoebaard’. It’s a pity that spelling didn’t persist: maybe less romantic, but tough as nails.)

Although the 1697 census records no children, this was likely due to a recording error rather than the loss of all three. By 1701, the records list six children – three boys and three girls – suggesting the earlier omission was simply a mistake.

Though he had many children, by 1758 – just 26 years after Pierre Joubert’s death – not a single one of his farms remained in Joubert hands. Their decline can be seen in figure two, which shows a clear decline in relative fortunes by the 1750s.

And yet, a century later, the Jouberts were back. In 1850, three brothers from the seventh generation owned farms once more in the Drakenstein district. Gideon Johannes Joubert (1805–1867) held Languedoc in Klein Drakenstein and Limietrivier in Agter-Groenberg. His brother Pieter Gideon Joubert (1810–1884) farmed Burgersfontein, also in Agter-Groenberg. The youngest, Jacobus Andries Joubert (1813–1900), owned Uitvlug in the Worcester district and Standvastigheid in Agter-Groenberg.2

What of the other names in Mosse’s novel? They appear less frequently. Most feature only once or twice in the censuses. (Again, see the figure above.) There is no Adriaan van Dijk, a fictional character, in the records – but there is an Adriaan van Wijk. He happens to have married Sara Fourie, the half-sister of my ancestor, nine generations ago. She was born in 1705, the seventh child of Louis Fourie. Twenty-nine years later, in 1734, my great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather Stephanus was born – Louis’s twentieth child. By then, Adriaan and Sara (Stephanus’s sister) had six children of their own.

I could not confirm the origin of the name Joubertspiek. But I don’t think it is unreasonable to imagine that it is named after Pierre Joubert, a refugee from France who, as Mosse’s fictional Suzanne believed, ‘had the strength of character to make a success of himself’ (p. 251). Whether or not that’s true, it is the man I’ll now associate with my morning ritual: the daily sunrise shifting from dark blue to bright yellow above Joubertspiek.

This post, ‘The Huguenot refugee’, first appeared on Our Long Walk. If you’d like to support more stories that bring the past to life through people, places and the traces they left behind, consider a paid subscription. I write more about the Huguenots in Our Long Walk to Economic Freedom, my accessible introduction to global economic history, told from a South African perspective. Kate Mosse will be speaking at the Franschhoek Literary Festival from 16 to 18 May, a fitting place to reflect on where fiction meets the past. The image was created using Midjourney.

The source here is the Bewaarders van ons Erfenis-database.

Here I again rely on the Bewaarders-database.

Lekker artikel, mede-fransman - paar typos - het 2 opgelet

Johan's qualitative research brings a new perspective to Huguenot history. An important reminder of their story is the well-marked long-distance trail, Sur Les Pas des Huguenots, completed in 2016, that traces the escape routes followed by refugees from the Drôme

region. When Louis Faurite left the Protestant stronghold of Livron, located at the confluence of the Rhône and Drôme rivers, in 1687, life for Protestants was unbearable. Their church had been razed in 1683 and exceptionally harsh dragonnades introduced in 1685. Louis XIV's revocation of the Edict of Nantes reduced them to second-class subjects, prompting mass abjurations and the flight of 3000 Drômois to the neighbouring Swiss cantons and German states.

To avoid royal troops and informers, Louis and his fellow refugees mostly walked by night, using ancient Roman roads, crossing Alpine passes on mule tracks, and bribing boatmen to ferry them across swollen rivers - such as the Isère in the shadow of Mont Blanc, at 4800m the highest peak in France. Taking risks could prove fatal: in November 1685, 45 refugees from Trièves in the Drôme, were massacred in broad daylight while crossing the Romanche River.

While the majority of Drôme Huguenots settled in the German states, particularly Brandenburg-Prussia, where they made up a quarter of Berlin's population by 1700, Louis Faurite and a few others found their way to the Cape of Good Hope.

Nowadays, parts of their gruelling journey can be retraced (on foot, by bicycle, or even with a pack donkey) along the 1600km trail, Sur les pas des Huguenots, https:www.surlespasdeshuguenots.eu/en/