The one advantage of living in Africa is that we all agree that it’s terrible to be poor.

A Malawian woman selling tomatoes by the roadside does not need a lecture on planetary boundaries. She knows what a higher income – growth – means: the chance to afford school fees, to replace a leaking roof, to buy a paraffin stove so she doesn’t have to cook over an open flame. Across the continent, a Nigerian entrepreneur is building a small factory, employing workers and raising capital. Growth is not a theory to him – it is the foundation on which he can build a future.

A new paper published in the prestigious journal The Lancet proposes that the Malawian woman and Nigerian entrepreneur are wrong. What they should care about, the authors of the paper suggest, is not higher incomes, better infrastructure, or economic opportunities, but wellbeing within planetary boundaries. They should not aspire to live as people do in high-income countries – no, that would be unsustainable. Instead, they should find fulfilment in a world with less. Less production, less consumption, less growth.

Perhaps this interpretation is too harsh. The most generous reading of the degrowth movement, as the authors of the paper claim to lead1, is that it calls for high-income countries to move beyond GDP as a policy goal, shifting their focus to redistribution, universal basic services, and reduced working hours to maintain employment and social stability without the need for continuous expansion. Under this view, poorer countries would still be allowed to grow – up to what is deemed a ‘sufficient’ standard of living. We should all live like Costa Ricans.

I’m sure Costa Rica is a beautiful place, but at the heart of this argument lies a fundamental misconception: that growth and sustainability are incompatible. The authors insist that economic expansion cannot be reconciled with environmental limits, that ‘absolute decoupling’ of GDP from emissions and resource use is a fantasy. But this is demonstrably false.2

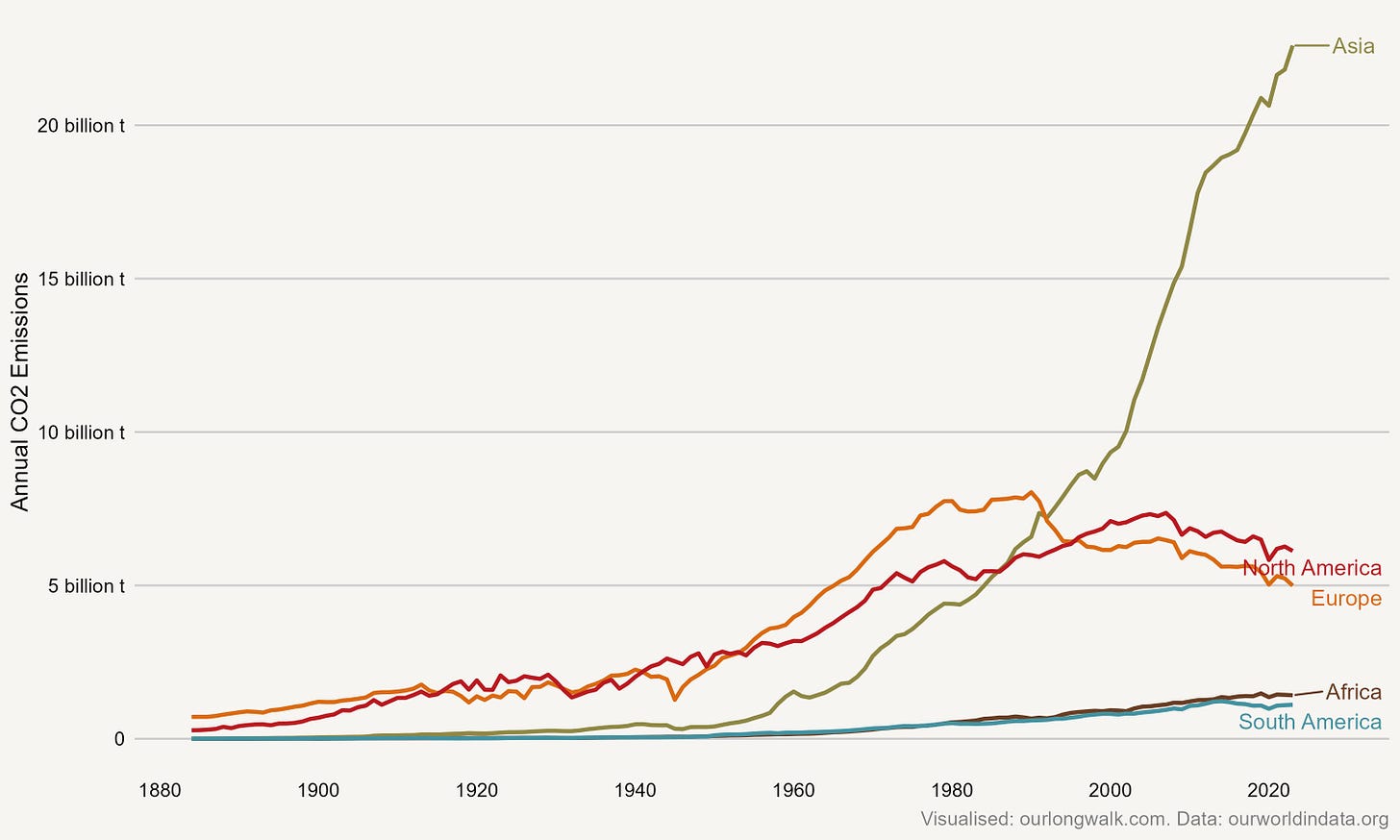

Many high-income countries have already decoupled emissions from economic growth. They produce more while polluting less. Take the graph above. It shows the annual CO2 emissions by continent. Though there is much one can say about the overall increases in Asia, notably China and India, it is very clear that emissions have fallen considerably in Europe since the 1990s and in the US since the 2000s.

The key lesson here is that renewable energy, carbon capture, precision agriculture, desalination, nuclear fusion and advanced battery storage are not the fruits of stagnation but of innovation, made possible by wealth. These are not inventions of countries that have deliberately capped their growth at the level of Costa Rica; they are the products of economies that invested in research, rewarded risk-taking and embraced expansion. The richer a country becomes, the more it can afford to clean up its industries, invest in efficiency and develop technologies that reduce its environmental footprint. The degrowth movement ignores this entirely.

The most revealing section of the paper is its discussion of political feasibility. The authors acknowledge that ‘economic and political systems are dependent on growth for their stability’ and that stagnation ‘poses substantial risks’. In plain terms, this means that without growth, governments struggle to maintain legitimacy. Political systems built on expanding opportunities begin to fracture when those opportunities disappear.

So how do the authors propose to manage this? Through greater state intervention. They argue for a ‘planned, democratic transformation of the economic system’ to ‘restructure the economy to be greener, healthier, and more equitable’. But who decides what is equitable? Who decides which industries should shrink and which should expand? A committee of appointed experts? A council of the enlightened –perhaps drawn from the authors themselves?

History has tested this before. Planned economies – from the Soviet Union to Maoist China – have repeatedly failed to deliver prosperity. They can suppress inequality, but only by ensuring that everyone is equally poor.

The irony is that these ideas emerge from places where comfort is taken for granted. (The nine authors are based in Spain, the UK, Canada, the USA, Switzerland, and Austria.) It assumes that economic growth is a luxury rather than the means by which billions escape hardship. It ignores the history of human progress – that wealth is not just more stuff but longer lives, better health and greater freedoms.

How do we save the environment?

It’s not news that humans are doing immense damage to the environment. Sir David Attenborough, wildlife expert and film maker, has been deeply concerned about the loss of biodiversity for decades. P…

That is why these ideas are also dangerous. It is an ideology uniquely suited to the incentives of academia: publish papers, secure grants and attract students eager to ‘fix’ the world. And just like the missionary movements of old, it is spread by well-meaning zealots convinced they are saving humanity, blind to the damage they cause.

And like all good missionaries, they are handsomely funded. In October 2023, the EU’s European Research Council handed €9.9 million to three of the authors of the present study to study degrowth. One assumes, given their convictions, that they will not pay themselves more than the global average income. In that case, this generous grant should last them for 541 years.3 And once they are successful in their work and the world economy shrinks, they may be able to stretch it for another seven or eight centuries.

I am being facetious, of course, but this calculation exposes the absurdity of it all. The degrowth movement flourishes not in places where poverty is real, but in well-funded academic circles where the material consequences of economic stagnation do not apply. Like a religious order exempt from the suffering it preaches, its adherents enjoy the benefits of growth while demanding others renounce them.

Degrowthers think they are being radical. In truth, they are deeply conservative. They fear change, reject risk and resist the forces that have lifted humanity from misery. A world without growth is not a world of balance and harmony – it is a world of trade-offs, where every gain for one person means a loss for another.

The real question is not whether we should grow but how. Growth does not have to mean more pollution or waste. It can mean cleaner energy, more efficient production and solutions to the very problems degrowthers claim to care about. As the Malawian woman and Nigerian businessman know only too well, prosperity is built, not rationed.

This is an edited and translated version of my monthly column, Agterstories, on Litnet. To support more writing like this, consider subscribing for a paid membership. The image was created using Midjourney.

The paper’s most revealing passage is:

“To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive review of the field. Unlike recent systematic reviews of degrowth, for example, which quantify emerging themes and gaps in the literature, our Review is an expert overview, written by leaders in the post-growth field, each specialised in one of its various branches.”

In other words: Unlike past research that systematically analyses evidence, this is a collection of views from those who already lead the movement – trust us, we know best.

This is a surprising way to approach a review. Rather than weighing up different perspectives, the authors position themselves as the final word on the subject, setting the terms of debate instead of engaging with it. This is not the language of open inquiry but of conviction – a sign that the answers have already been decided.

Even the authors acknowledge this. They state emphatically that ‘there is no evidence of sustained absolute decoupling’, yet a few paragraphs later, they mention that ‘absolute decoupling of GDP from emissions occurred in several high-income countries, even accounting for trade’.

€9,900,000/(€16.72*365*3) = 541 years

Thanks Johan, thought-provoking read. I should probably go and look on Litnet but if you are up for answering a quick question, what would the Afrikaans word be for degrowth?

This is Wealth NIMBY (Not in my back yard). Wealthy reserchers and writers believe they can persuade the have-nots to forgo the bought privileges and goodies that they consume to protect their own consumption of those self same privelages and goodies