In August 2024, Andrew Whitfield, South Africa’s Deputy Minister of Trade, Industry and Competition, posted a picture of Dmitry Grozoubinski’s Why Politicians Lie About Trade … and What You Need to Know About It on LinkedIn, with the following inscription:

Makes for interesting (sometimes awkward) reading about the world of trade policy and it’s (sic) implications for economies and politicians 😅

Whitfield had just returned from a trip to the United States, where he and the Minister, Parks Tau, attended the 21st Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) Forum. The tone then was upbeat. ‘Minister Tau concludes a successful visit to the United States’, proclaimed the Department of Trade, Industry and Competition. ‘There was broad support for strengthening bilateral trade and investment relations between South Africa and the United States.’

Eight months is a long time in politics.

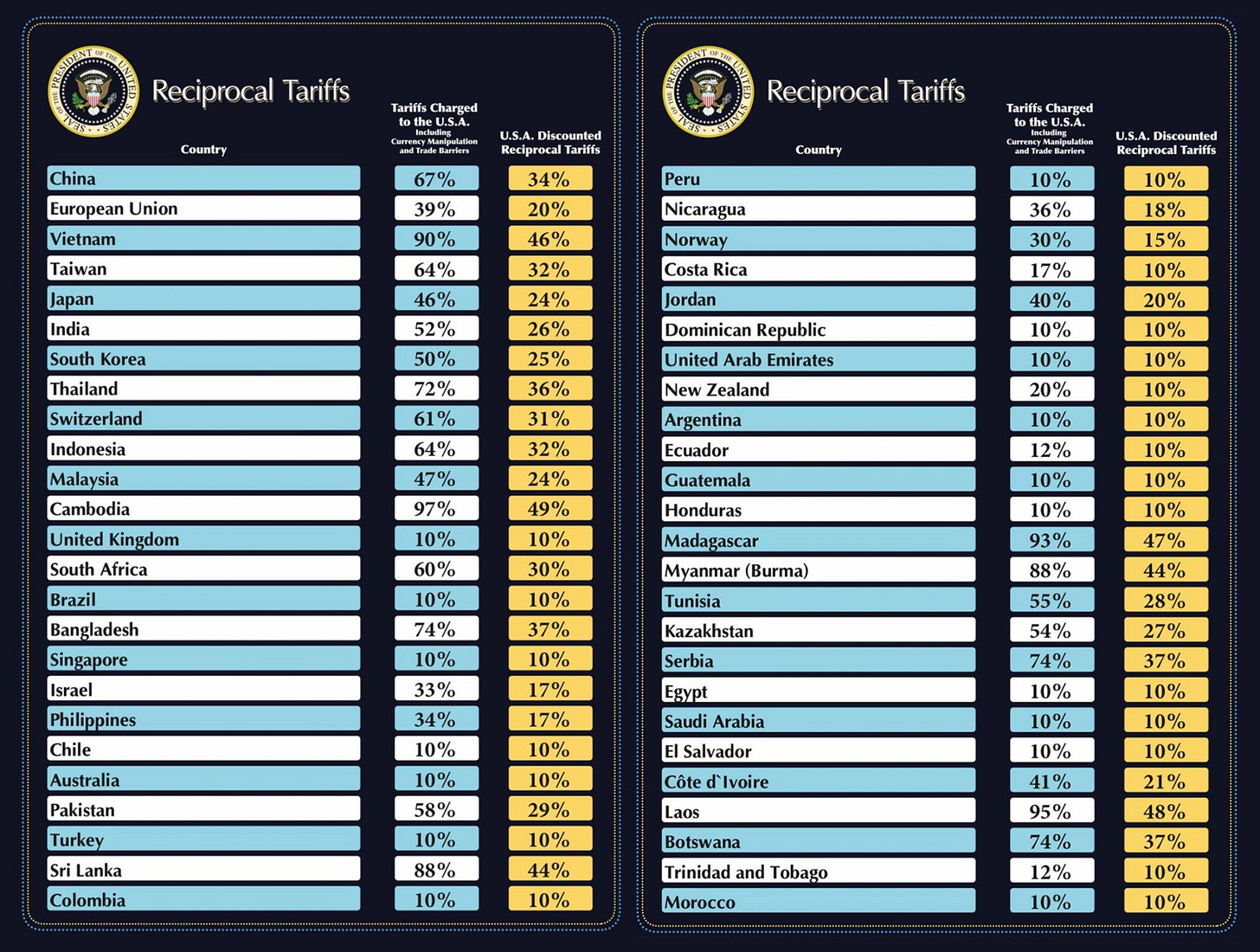

On Wednesday evening (SA time), US president Donald Trump announced what he called ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs on imports to the US. South African importers were handed a particularly painful penalty: a 30% tariff, apparently because ‘South Africa, they got some bad things going on’.

In what follows, I do three things. First, I assess the accuracy of Trump’s tariff claims. His claims, I suggest, reveal more about his political strategy than any real trade offence. I then explore the economic rationale behind the new Trump tariff doctrine. Finally, I ask: how should South Africa respond?

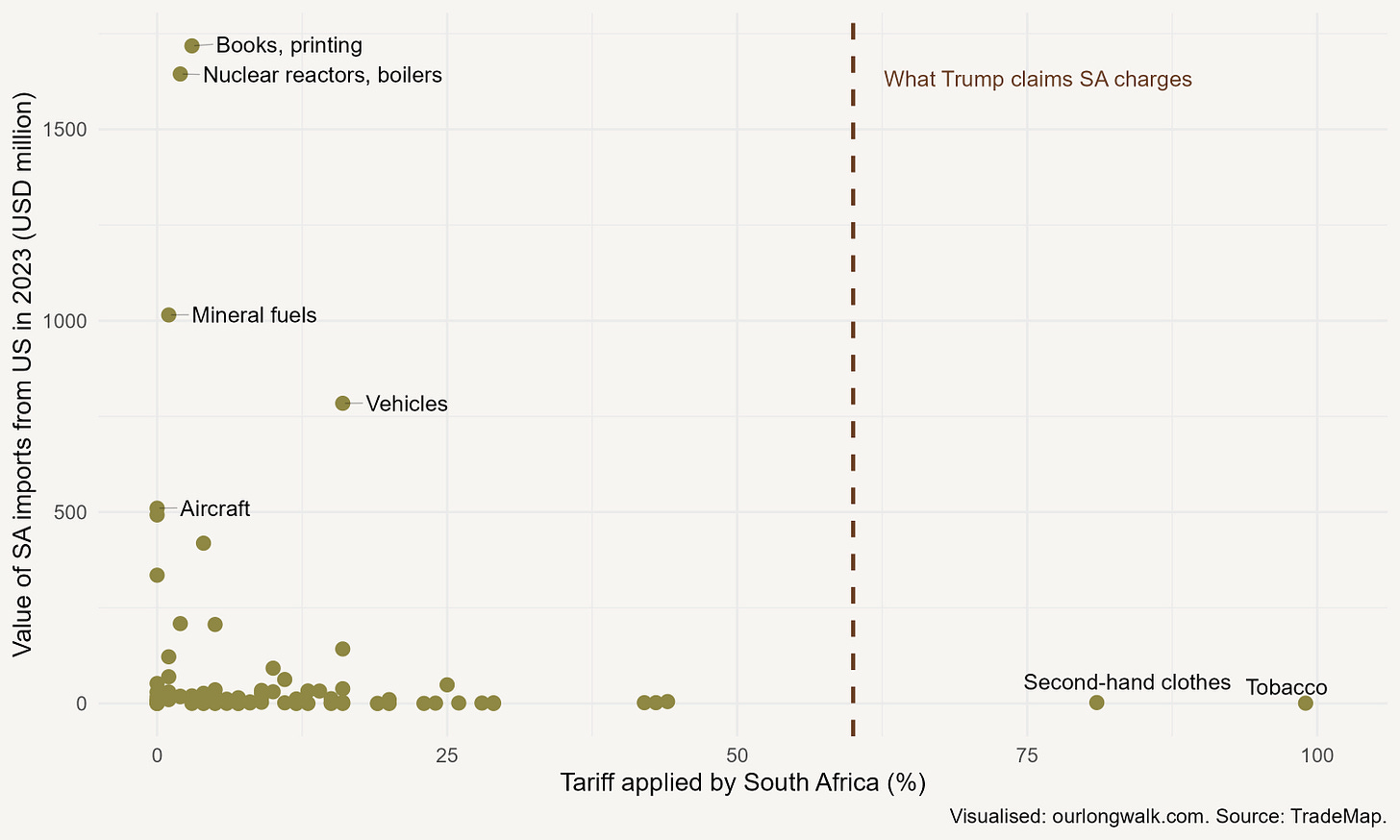

Let’s start with Trump’s central claim: that South Africa imposes a 60% tariff on US imports. This is incorrect. Plain and simple.

The scatterplot below – based on data from TradeMap – shows the tariff imposed by South Africa on each two-digit product category imported from the US in 2023. The vertical axis measures the value of imports in millions of US dollars; the horizontal axis, the tariff percentage.

What’s immediately clear is that only two product categories face tariffs above 60%: second-hand clothes and tobacco. These are also among the smallest in value. At the six-digit product level – where there are more than a thousand categories – only four US imports face tariffs of 60% or more: worn clothing and accessories (175%), two kinds of tobacco (between 111% and 145%), and canned tomatoes (60%). Together, the total value of the high-tariff imports was just $379,000 in 2023, so small it is basically a rounding error.

South Africa, in short, does not impose anything close to a 60% tariff on US goods. So how did Trump arrive at that number?

The method appears to have little to do with actual trade policy. Instead, a country’s so-called ‘tariff’ on the US was derived from a crude formula: take the US trade deficit with that country, divide it by US imports from that country, and call the result their ‘tariff’. Trump then imposed a reciprocal tariff equal to roughly half that number.

Take South Africa. In 2024, the US imported $14.7 billion in goods from South Africa and exported $5.9 billion, resulting in a trade deficit of $8.8 billion. Divide $8.8 billion by $14.7 billion and you get about 60%. Trump’s team then sets the ‘reciprocal’ tariff at 30%.

This is economically nonsensical.

Worse, the calculation above ignored services, where the US often runs surpluses. A country may import billions in US digital or financial services – and it simply doesn’t count. Only goods are considered.

This approach confuses a trade imbalance – which reflects exchange rates, global demand, and comparative advantage – with protectionism. It implies countries running surpluses with the US are cheating, even when trade flows are shaped by market forces.

The rationale becomes clearer, though, when you follow the intellectual blueprint. In November 2024, Stephen Miran – now Chair of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisors – published a 43-page roadmap titled A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System.

It’s a revealing document. The central thesis is that the overvaluation of the dollar – due to its reserve currency status – has hollowed out US manufacturing, caused job losses and forced America to run persistent deficits. Tariffs, Miran argues, can help rebalance this by generating revenue, reducing imports and shielding critical industries.

He suggests tariffs, if offset by currency adjustments, need not be inflationary. In fact, if the exporting country’s currency weakens (as China’s did after the 2018 tariffs), the US can raise billions in revenue while domestic prices stay stable. That money, in turn, can be used to fund America’s role as the provider of global security and reserve assets.

Yet many of the claims in the document are dubious. Miran, for example, argues that ‘value-added taxes (VAT) are a form of tariffs because they exempt exported goods but tax imported goods’. As Scott Sumner writes on Substack:

Public Finance 101 says this is wrong. A VAT is a consumption tax. It excludes exports and includes imports because exports are not a part of domestic consumption and imports are. A VAT differs from a tariff in that the tax applies equally to both domestically manufactured goods consumed locally and imported goods consumed locally. Perhaps I’m missing something (and please help me out if I am), but Miran’s remark makes no sense to me.

And it’s all downhill from there.

Indeed.

Trump clearly sees tariffs as a way to raise revenue, a substitute for politically unpopular tax increases. But, just a reminder, trade theory and economic history suggest this is a suboptimal approach. Tariffs distort prices, reduce efficiency and invite retaliation. The idea that tariffs can painlessly fund government or ‘reshore’ manufacturing is a fantasy that economists debunked long ago.

A second justification offered for the tariffs is the need to support domestic manufacturing – a classic argument for protectionism. The idea is that certain industries are too important to national security to be left exposed to foreign competition. The steel industry. Pharmaceuticals. Semiconductors. The rhetoric is familiar: if a nation cannot produce its own weapons or antibiotics, it cannot defend its sovereignty.

Granted, the theory of strategic trade protection suggests that temporary protection may be warranted where markets fail to deliver optimal outcomes – for instance, where there are learning-by-doing externalities or where first-mover advantages in high-tech industries might generate lasting national gains. In such cases, a carefully designed policy might nurture an industry to global competitiveness.

But that’s not what is happening here.

The Trump administration has imposed sweeping tariffs under the guise of a national emergency. The mechanism used – Section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974 – requires evidence of serious injury to domestic firms. In most of these cases, that threshold has not been demonstrated. And even if it was, the remedies are meant to be temporary and proportionate – not universal and punitive.

What is clear is that this is not about shielding vulnerable industries from unfair competition. It is, instead, protectionism in emergency clothing.

Although the US Congress may still reverse these tariffs, the reality is that, come next week, South African producers will face massive tariff barriers exporting their goods to the US. How, then, should South Africa respond?

The instinctive response might be to impose counter-tariffs. But that would be short-sighted. Economic theory warns against retaliation – especially for small, open economies. Tariffs may protect domestic firms in the short term, but the costs quickly mount: We risk losing access to export markets. Input prices rise as global supply chains are disrupted. Trade is diverted from efficient partners to less efficient ones, raising costs for consumers.

Yes, retaliatory tariffs can serve a political signalling function – a show of resolve. But when the opponent is a behemoth like the United States, such a strategy is risky and potentially self-defeating. The risk of disproportionate harm is high. Rather than escalate, South Africa – which, lest we forget, struggled to finalise its national budget just this week, exposing the fragility of its policy coordination – would do well to proceed with caution.

First, it should avoid being drawn into performative retaliation. Trade negotiations take time and are conducted behind closed doors, not on social media or through public grandstanding. Tit-for-tat tariffs are more likely to harden positions than to produce constructive outcomes.

Second, Trump’s list targets individual countries – not trading blocs. This reflects his preference for bilateral confrontation, where power asymmetries can be exploited. South Africa should respond not as a lone actor, but as part of a collective voice. It should insist on speaking as part of the Southern African Customs Union (SACU), or better still, under the banner of AGOA or the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). This both dilutes the imbalance and signals a commitment to regional coherence and long-term integration.

Third, South Africa should use these same blocs to deepen economic ties beyond the US. The European Union, ASEAN, India, Latin America and Commonwealth partners all offer opportunities for greater trade integration. Bilateral and multilateral agreements with like-minded regions can strengthen resilience and reaffirm a commitment to the open, rules-based global trading system that has underpinned global growth since 1945.

Although Trump will say many things to justify high tariffs – from migration control to fentanyl reduction, from currency manipulation to land expropriation laws – the economic rationale for the high tariffs is clear if you accept the flawed premise: tariffs provide revenue. That both explains their appeal to Trump and undermines any attempt at countering these measures.

I hope Minister Whitfield read all the way until page 212 of Dmitry Grozoubinski’s Why Politicians Lie About Trade. There, Dmitry writes:

I think we can also fully expect some of the measures … to be nakedly protectionist, impurely motivated, and questionably effective even when measured against their own stated objectives…

How disruptive all this proves to business, how damaging to growth and development, and how stifling to innovation and long-term investment will depend on the restraint shown by both sides, the extent to which a cycle of policy action and retaliation becomes self-perpetuating, and how other countries react from the sidelines….

In other words, we’re in for a wild ride.

The world of trade policy and it’s (sic) implications just entered its autumn of autarky. 😧

An edited version of this article was published on News24. Support more such writing by signing up for a paid subscription. The images were created with Midjourney v6.

Trump’s tariff rate calculations is economically stupid, but politically simple. Ordinary Joe or Karen in the street will understand it, even defend it, no matter what economists argue. I’ve had similar economically illiterate arguments with people in the past.

My few notes on this:

- key principle for a response must be to minimise harm to SA producers & consumers, taking into account who in SA import goods from the US & export to the US. E.g. could SA levy a surcharge on all USD forex transactions of say 0.5%-1%? Or maybe additional charge of 5%-10% for import of any US services, including finance? Ideally the repsonse should be less punitive but more supportive of SA industry where possible.

- government should assist SA producers to seek alternative markets for SA goods, & best to look at markets which are supplied by exports from the US (eg Africa & mid-east)

- lots of goods from all over the world which were exported to the US may now look for alternative markets, incl. vehicles from Europe, clothing from Bangladesh & Vietnam, etc. this could lead to them “dumping” these in SA, so we should implement policies to prevent/minimise this as much as possible.

- the global environment is as good as its ever been to resolve the Denel situation, either through partial privatisation, sub licensing Denel IP &/ sub-lease Denel production capacity for foreign defence manufacturers, etc. taking into account global & regional geopolitics.

Trump's single minded focus on trade deficit as metric is puzzling to me. I have a very successful 100% trade deficit with my local grocery store.

Not having to spend my entire day raising my own chickens, milking my own cows, and growing my own wheat frees me up to do much more profitable things. Both me and my grocer benefit. If we didn't, there would be no transaction.